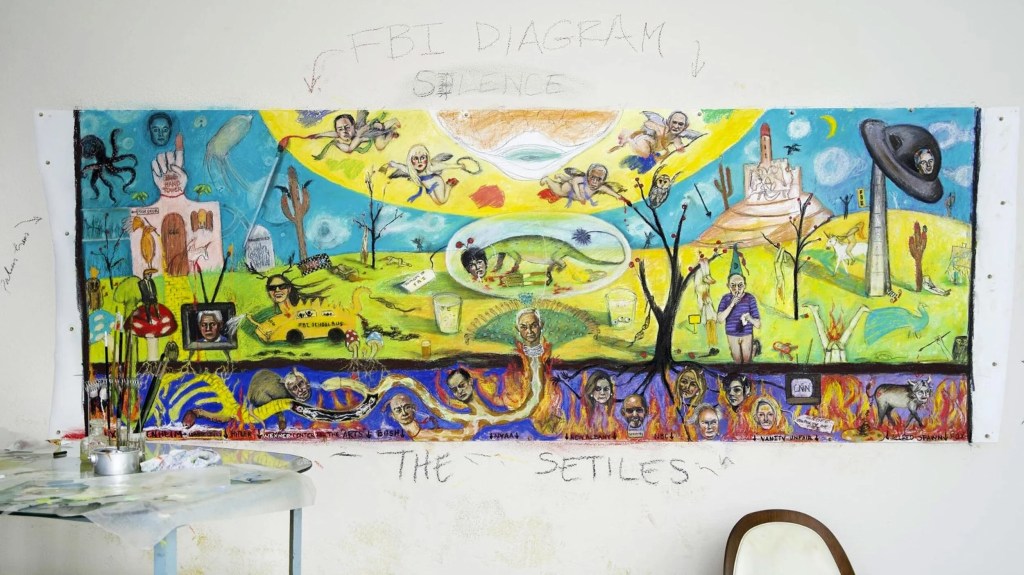

Maria Farmer’s “The Setiles” is not merely a painting, but a visual document, an illustrated web of abusers, enablers, and survivors, wrapped in symbolism that channels biblical, mythological, and modern cultural anxieties. Drawing on themes found in the Book of Revelation, infamy surrounding the cult of Moloch, and the iconography of elite rituals, Farmer’s painting serves as indictment, prophecy, and witness. Here, every brushstroke speaks in allegory.

⸻

the Beast, “666,” and multi-headed networks

One of the most visually jarring aspects of “The Setiles” is its direct invocation of apocalyptic scripture. The “666” above a central doorway calls forth Revelation’s prophecy of a beast whose name is a number.

“This calls for wisdom: Let the one who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man, and his number is 666.” – Revelation 13:18

In Farmer’s universe, this is not only a nod to collective evil, but also an explicit indictment of the complex network surrounding Jeffrey Epstein.

head of the snake and seven-headed beasts

Les Wexner is painted as the literal head of a snake, reinforcing his pivotal role in the wider syndicate and acting as a visual echo to the seven-headed beast of Revelation. But Farmer’s symbolism doesn’t rest with biblical evocation: the snake winds throughout the human architecture of the painting, suggesting both original sin and the cunning, relentless nature of predatory power.

“And I saw a beast rise up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns; and upon his horns ten crowns; and upon his heads the name of blasphemy.” – Revelation 13:1

the octopus and power’s tentacles

Farmer includes an unmistakable octopus with seven tentacles, deliberately chosen to signal the “Octopus Syndicate” theory, each tentacle representing a facet of elite control (finance, law, intelligence, media, government, social clubs, and the fashion industry). This mirrors modern speculation about interlocking circles of influence and is a direct artistic analog to the multi-headed beasts of Revelation, where corruption is systemic, not isolated to one villain.

⸻

temples, babylon, and the tree of poisoned fruit

temple structures and ritualized spaces

In “The Setiles,” temple-like buildings are scattered throughout, one reminiscent of the infamous blue-and-white temple from Epstein’s Little St. James. The architecture of secrecy is itself an accusation, inviting parallels to Revelation’s “Babylon the Great,” the whore city built on power, money, and secret rites (Revelation 17–18). Farmer’s temples are ambiguous: are they havens, prisons, or sites of ritual corruption?

“Come, I will show you…the great prostitute who is seated on many waters…Babylon the Great, mother of prostitutes and of earth’s abominations.” – Revelation 17:1, 5

“tree of deadly apples” and forbidden knowledge

Central to the painting is the “tree of deadly apples.” Here, Farmer connects biblical motifs (the Tree of Knowledge, Eden) with the fruit of corruption: each apple is a poisoned gift, and at the roots are media figures like Graydon Carter and Vicky Ward, depicted as drawing nourishment from the same corrupt soil. This is not only a condemnation of those who directly commit crimes, but also those who enable, profit from, or turn a blind eye to systemic abuse.

“Fallen! Fallen is Babylon the Great!’ which made all the nations drink the maddening wine of her adulteries.” – Revelation 14:8

arrows and gateways

Arrows pointing to secret doors or “floor doors” hint at routes into clandestine operations, secret societies, and the hidden architecture of crime. It may also reference Masonic, Luciferian, or other occult imagery, doorways as portals to knowledge (or, here, abuse), with Farmer inscribing warnings directly onto these thresholds.

⸻

martyrs, skeletons, and the underworld

bones beneath the tycoons

Beneath power figures, Farmer paints the skeletons of girls, an artistic testimony to victims both literal and symbolic.

“And when he had opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God…And they cried with a loud voice, saying, How long, O Lord, holy and true, dost thou not judge and avenge our blood?” – Revelation 6:9-10

Prince Andrew and Sarah Kellen (in a school bus), sit atop bones, referencing the cost that comes with their wealth, predation, or “protection.” The bones echo the souls of martyrs beneath the altar in Revelation, combining scripture’s promise of vindication with a raw reminder of loss and the normalization of hidden atrocity.

depictions of hell and judgment

The lowest levels of the painting resemble Bosch’s hellscapes: urinating and defecating figures signify both degradation and the destruction of innocence, the reduction of lives and dreams to waste. Alan Dershowitz, pantsless, and Ghislaine Maxwell, devouring a schoolgirl, are painted into this landscape as both actors and consequences, reinforcing the sense of all-consuming judgment that underpins Revelation.

“And I saw a great white throne…And the dead were judged…according to their works: – Revelation 20:11-12

⸻

animal, occult, and surreal symbolism

owls

Farmer’s owls serve multiple functions. They can represent wisdom, but here they have darker tones: surveillance, complicity, and the presence of the “watchers.” In conspiracy and occult culture, the owl is sometimes (controversially) linked to Moloch or secret societies like Bohemian Grove. Farmer positions the owls where they oversee, sometimes crowned, perhaps suggesting “kingmakers” behind the scenes, those who know the full truth yet act as hidden sentinels.

peacocks

Her peacocks, detailed with phallic feather patterns, double as references to “peacocking” (sexual bravado and display), satirical commentary on the hypersexual power dynamics of elite circles, and even esoteric symbols for resurrection or the soul’s beauty. The sexual nature of these birds in Farmer’s composition adds a further layer of critique, highlighting how sexuality was weaponized and corrupted in the network.

reptiles and monsters

Lizard Ghislaine Maxwell (biting a schoolgirl’s head off with pearls around her neck) and the snake Wexner point to ideas of “cold-blooded” operation: unfeeling, predatory, non-human. The recurrence of snakes and lizards, instead of warm-blooded animals, implies a lack of empathy and the evolutionary “reptilian brain,” associated in pop psychology and conspiracy lore with ruthlessness, dominance, and secret societies.

“And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world…” – Revelation 12:9

mushrooms

Mushrooms, possibly psychedelic, are spread throughout. They suggest both altered reality (hallucination, cognitive distortion), and, in a Jungian sense, “underground networks” or the hidden mycelium of abuse beneath the public surface. They may also nod to themes of intoxication or the spiritual “haze” that allows evil to remain unchallenged.

⸻

moloch, cult worship, and ritual sacrifice

carrying ancient fears forward

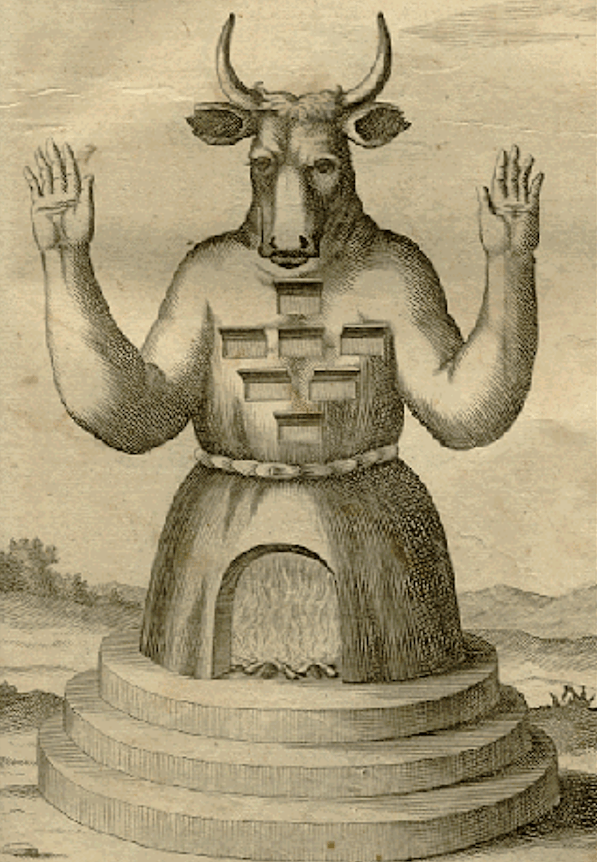

The theme of child sacrifice underpins many of Farmer’s accusations, not merely physical, but spiritual and social. Images of children as prey, skeletons beneath powerful men and women, and the “unworthy” circle illustrate a modern vision of sacrifice for gain, reminiscent of biblical and mythic warnings.

“And thou shalt not let any of thy seed pass through the fire to Molech…” – Leviticus 18:21

temple as site of abomination

Echoing the rumors surrounding Epstein’s island temple, these structures in the painting suggest modern ritual sites, where abuses occurred far from the world’s gaze, cloaked in the trappings of power, secrecy, and ancient evil. The suggestion is unmistakable: some modern elites, through commission or omission, reenact the central horror of Moloch worship, destroying innocents to perpetuate their own power.

ritualistic animal imagery

While true “ritual abuse” is hotly debated and often sensationalized, the presence of cows, bulls, owls, and snakes in “The Setiles” layers the message. Abuse becomes not just a crime, but a perverse rite, repeated across generations and institutions.

⸻

survivors, cherubs, and visual testimony

the survivors’ palette

In contrast to the infernal imagery, Farmer paints survivors with unique, bright backgrounds, turquoise, pink, yellow, green, and orange. Each color is meant to celebrate individuality and resilience, a deliberate counterpoint to the sameness of abusers. Survivors are depicted as icons to be honored, not shamed.

“These are they which came out of great tribulation…and God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes.” – Revelation 7:14-17

cherubs and guardian spirits

Farmer’s own lawyers appear as cherubs, celestial defenders watching over the battle. These figures, reminiscent of Renaissance archangels, hold paintbrushes or shields, offering both hope and reassurance that even in hellish landscapes, pockets of justice and advocacy endure.

reclaiming power through art

Farmer’s narrative is not merely personal. She positions her work as evidence for the authorities, “an illustration for the FBI,” and a way of saying what was ignored when spoken aloud. Her artistry becomes an act of spiritual warfare against the silence that protects abusers.

⸻

conclusion: painting as prophecy and protest

Maria Farmer’s “The Setiles” is at once a chronicle, an accusation, and a scripture of survival. Every figure, object, and creature within is layered with witness, warning, and lament. With relentless allegory, from Revelation’s apocalypse to the eternal threat of Moloch’s cult, Farmer’s work calls for a reckoning that is legal, spiritual, and deeply personal. The painting insists on one central truth: every system built on sacrifice of the vulnerable must one day be named, and, ultimately, judged.

⸻

Stay curious.

⸻

sources

- King James Version with passages cited directly:

Revelation 13:1, 13:18, 6:9-11, 7:14-17, 12:9, 14:8, 17:1,5, 20:11-12, Leviticus 18:21

Leave a comment