“The various modes of worship which prevailed in the Roman world were all considered by the people as equally true; by the philosophers as equally false; and by the magistrates as equally useful.”

– Edward Gibbon (The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire)

There’s a pattern that repeats across empires, and it rarely looks like conquest from the inside. It looks like tradition. It looks like order. It looks like something passed down from a time when things supposedly made more sense. But when you look at it without the seasonal packaging or institutional polish, what you see is a control system built on ritual repetition—justified by myth, sustained by calendars, and enforced by the illusion that the structure is inevitable.

Saturnalia wasn’t a winter festival of joy and equality—it was a performance. A calculated, time-boxed ritual of disorder used to reinforce the existing power hierarchy while giving the appearance of subversion.

The god it celebrated—Saturn, or Kronos in Greek tradition—wasn’t a harmless mythological figure. He was a symbol of absolute control. According to the myth, Kronos overthrew his own father and then turned around and ate each of his children as they were born to prevent the same from happening to him. It’s a narrative where power justifies anything to preserve itself, even cannibalizing the future.

And while we don’t literally believe in gods who eat their children, we do participate in systems that follow the same logic—prevent disruption before it starts, absorb opposition before it organizes, and reset the cycle before anyone questions who’s really benefiting from it.

⸻

saturnalia and the illusion of reversal

Saturnalia began around December 17th on the Roman calendar and eventually stretched into a full week. Work stopped, schools closed, courts were suspended, and social norms were inverted. Slaves were allowed to speak freely, wear fine clothes, and even be served meals by their masters. A mock king—known as the “Lord of Misrule”—was crowned and granted symbolic authority. Public gambling, drunkenness, and street celebrations were not only tolerated but expected.

But none of this represented a real threat to the Roman hierarchy. In fact, it was part of how that hierarchy maintained itself. The ritual inversion was temporary, contained, and officially sanctioned. It gave people a structured release, a narrow window for chaos, and a clear endpoint where the normal order of things would resume—if anything, more firmly entrenched than before.

By design, it functioned as a system of pressure relief. People were allowed to mock their superiors, break taboos, and engage in behaviors that would be punishable the rest of the year. But it was clear to everyone involved that the inversion wasn’t permanent, and stepping outside the ritual bounds of Saturnalia would still get you punished. The ritual was about reminding everyone that even their rebellion had a time and a place assigned to it.

⸻

the transition from pagan feast to christian holiday

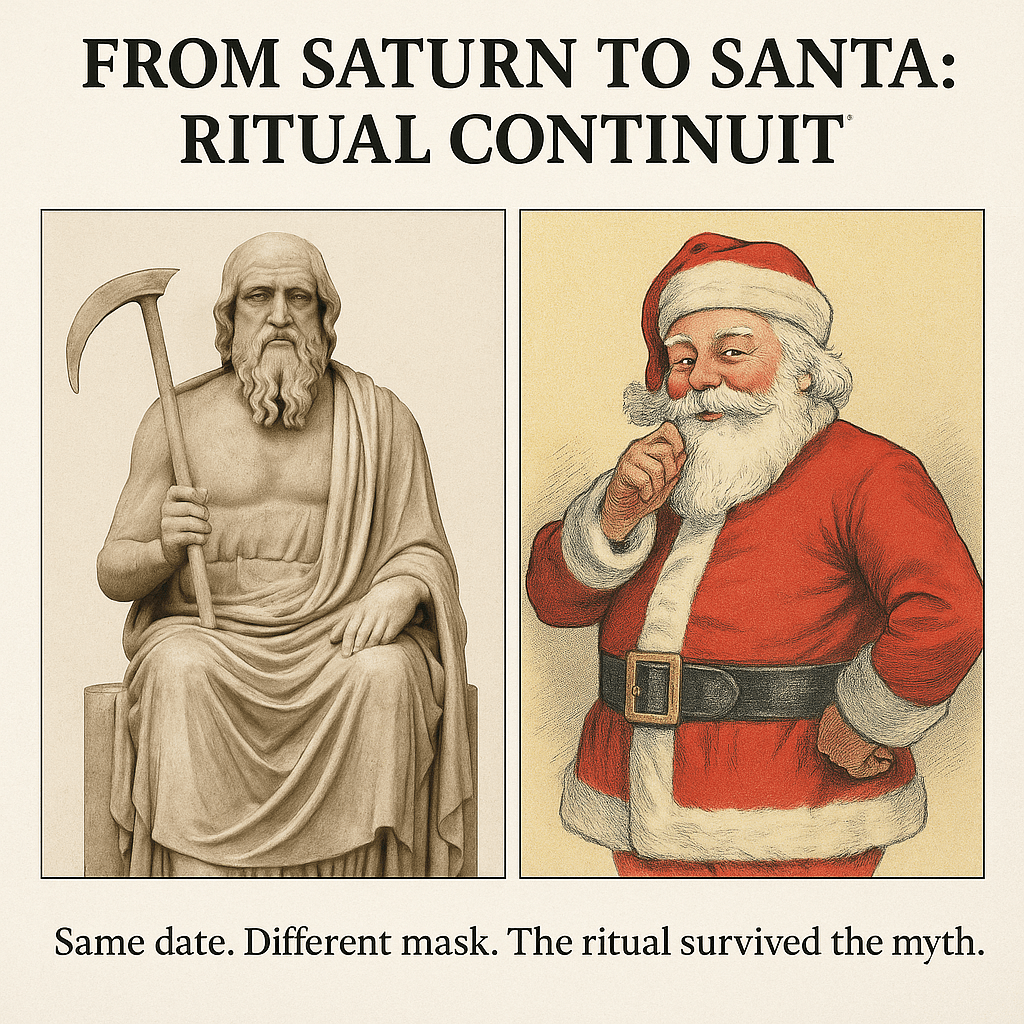

When the Roman Empire officially adopted Christianity, the leadership didn’t wipe Saturnalia off the map. They rebranded it.

“The Church did not so much destroy pagan traditions as absorb them, giving Christian names to ancient festivals and overlaying new meanings on old rituals.”

— Thomas Cahill (Historian, How the Irish Saved Civilization)

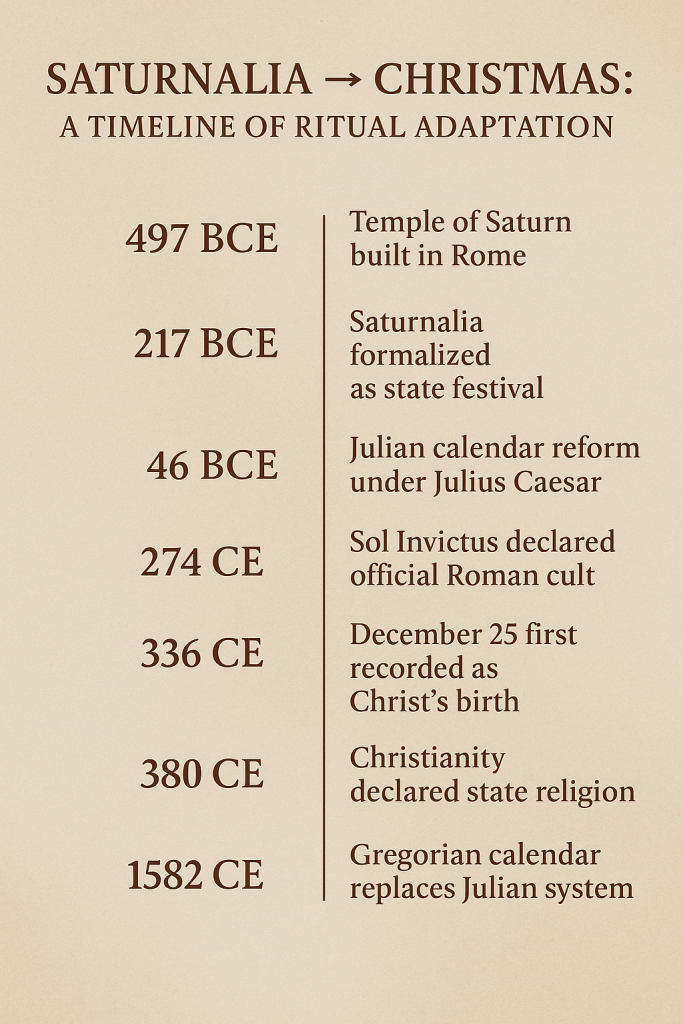

By the 4th century CE, Church leaders had a problem. Saturnalia was still popular, and despite attempts to stamp it out, it remained embedded in the culture. Rather than banning it outright—which would’ve caused backlash—they layered new meaning onto the same dates. December 25th, originally associated with the rebirth of the sun god Sol Invictus, was recast as the birth of Jesus Christ. Sol Invictus itself had been a syncretic stand-in for older deities like Mithras and, in some interpretations, Saturn.

The core structure of Saturnalia—the timing, the themes of renewal, light emerging from darkness, celebration in the midst of winter—was retained. The aesthetics shifted, but the rhythm stayed. What had been a festival for a god of time and control became a holiday for a savior figure. But the calendar didn’t forget. And neither did the institutional structures that used it to manage behavior.

⸻

calendars as infrastructure

The Roman calendar was already a tool of imperial administration. It was used to organize military campaigns, tax collection, and civic events. Julius Caesar’s reform of the calendar in 46 BCE—the Julian calendar—wasn’t just about aligning with the solar year. It was about syncing the empire to a standardized framework. It was about power knowing where everyone stood, and when.

The Julian calendar introduced a 365-day year with a leap day every four years. It aligned religious festivals, harvest schedules, and civic life in a way that let the state manage its subjects more predictably. When the Gregorian calendar replaced it in 1582 (under Pope Gregory XIII), the goal was the same: recalibrate time to maintain control. The Church needed Easter to line up with the equinox again, and the drift in the Julian system was throwing off the ritual calendar.

Timekeeping reforms were always about maintaining institutional legitimacy. The calendar told people not just when to plant crops or pay taxes, but when to celebrate, when to mourn, and when to feel spiritually aligned. It became a psychological framework as much as a logistical one.

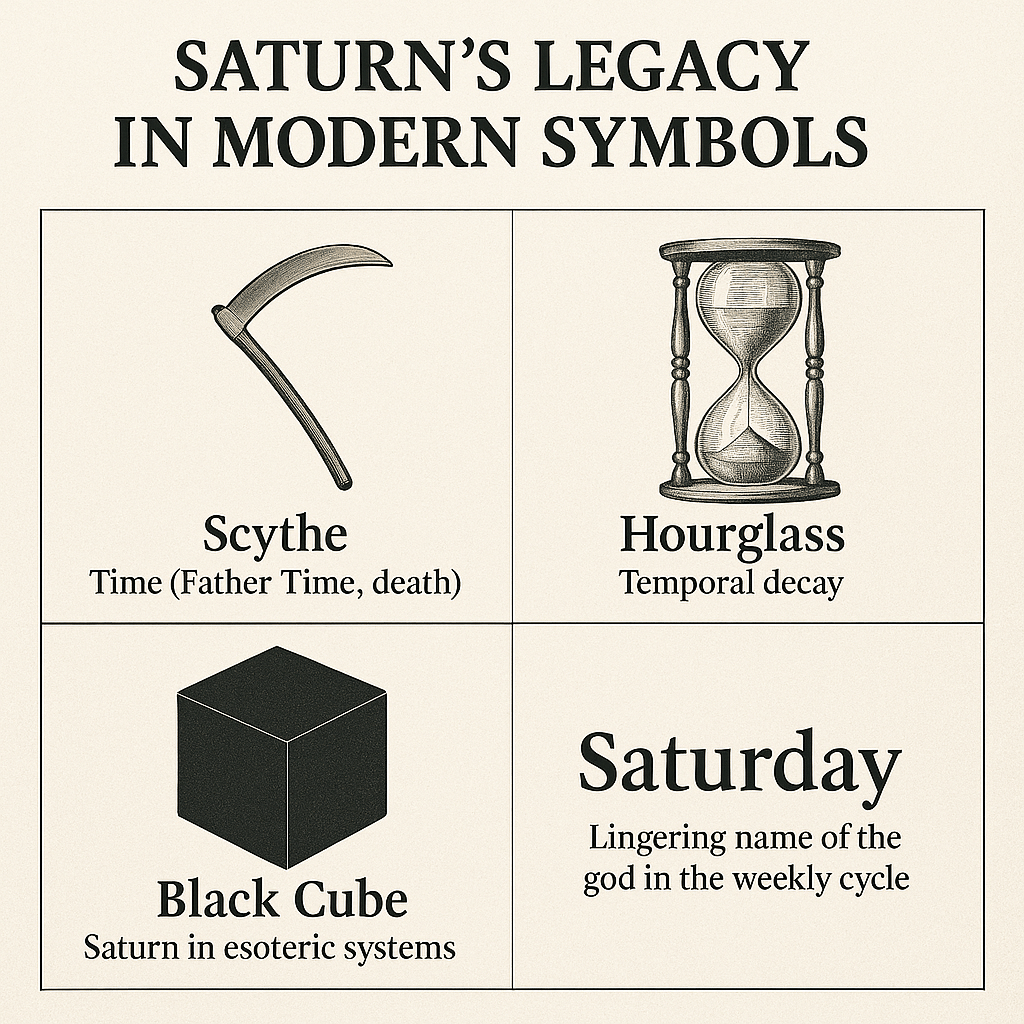

Saturn, as the god associated with time, structure, and cycles, became invisible—but his logic remained baked into the infrastructure.

⸻

from ritual to operating system

By the modern era, the ritual logic of Saturnalia had long been absorbed into secular culture. Holidays like Christmas and New Year’s retain the inversion structure: excess followed by restraint, indulgence followed by resolution, year-end release followed by return to order. The Church no longer needs to enforce the calendar’s authority. The state doesn’t need to mandate celebration. The rhythm is internalized. It’s built into payroll systems, shopping cycles, school calendars, and cultural expectations.

The so-called “holiday season” is heavily commercialized, but that’s not a corruption of some pure spiritual ideal. That’s the logical outcome of a ritual system built on release and reset. Saturnalia was always about scheduled chaos. Now it runs on algorithms.

Black Friday is not a capitalist invention in the abstract—it’s a repackaged Saturnalia ritual, one that gives you permission to transgress (shop, indulge, break budgetary norms) within a defined window before the system reasserts control in January with resolutions, productivity drives, and tax season looming.

What was once a Roman god’s feast has become a commercial protocol.

⸻

institutional memory and systemic continuity

The myth of Saturn eating his children isn’t some ancient allegory with no modern relevance. It describes a form of institutional self-preservation that still exists. Systems—whether religious, political, or economic—often preemptively neutralize disruption by incorporating its symbols, redirecting its energy, or scripting its expression.

Saturnalia, as an inversion ritual, allowed the Roman state to simulate instability without actually risking collapse. The Church absorbed its rhythms because it understood that suppressing popular tradition outright rarely works in the long term. And modern systems continue the pattern: simulation instead of substance, managed dissent instead of actual disruption.

We don’t need to believe in Saturn as a deity to recognize his function as a symbol. Not a mythological figure, but a shorthand for the architecture of ritualized control. His legacy isn’t just in a statue or a story—it’s in the clock, the fiscal quarter, the calendar invite, and the social script that tells you when to act out and when to shut up.

Stay curious.

⸻

Coming in Part II:

The transformation of Saturn’s control logic into digital systems:

From Chronos to clocks, from Church feasts to fiscal years, and from behavioral rituals to predictive algorithms.

Leave a comment